INTRODUCTION

Obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, is a complex, multifactorial disease, with an increasing public health and economic impact.1–3 The World Health Organization has estimated that more than 890 million adults aged 18 years and older were living with obesity worldwide, as of 2022.2 Mirroring this global trend, the prevalence of obesity has been steadily increasing in the United Kingdom (UK). According to the Health Survey for England, the prevalence of obesity in England was estimated at 26% among adults in 2021.1

People living with overweight or obesity (PLwO) are at an elevated risk of experiencing chronic comorbidities, multimorbidity, and mortality.4 In the Global Burden of Disease study, cardiovascular disease (CVD) emerged as the greatest cause of disability and deaths related to high BMI (≥25 kg/m2) worldwide in 2015.5 More than two-thirds of deaths related to high BMI were due to CVD, which accounted for about 2.7 million deaths and 66.3 million disability-adjusted life-years.5 Type 2 diabetes (T2D) was the second leading cause of deaths related to high BMI in 2015, contributing to 0.6 million deaths and the loss of 30.4 million disability-adjusted life-years.5 Published data suggest that health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is lower for people with overweight (defined as BMI 25 to <30 kg/m²) or obesity than for those with normal weight (defined as BMI 18.5 to <25 kg/m²).6,7 However, detailed data exploring the effects of different comorbidities on physical and mental HRQoL in PLwO are limited.

In 2022, the annual total cost of obesity in the UK, including all National Health Service (NHS), individual, and societal costs, was estimated at £58 billion.8 By far the largest proportion of these costs, at 69%, was attributed to the individual impact of a reduction in quality of life (QoL), expressed in quality-adjusted life-years. Treatment of obesity-related diseases accounted for 11% of costs, and lost productivity for 3%.8 Extensive evidence indicates that comorbidities in people with obesity are a major driver of healthcare resource utilization and costs.9–11 However, data are limited on the associations between BMI, comorbidities, and work productivity.

In this study, we addressed current evidence gaps by using data from a survey of physicians responsible for managing obesity and PLwO who were receiving weight management support, to examine the relationships between BMI, comorbidities, and self-reported HRQoL and work productivity in PLwO in the UK.

METHODS

Data Source

Data from the Adelphi Real World Obesity Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP) were used in the analyses. Briefly, the DSP is a large, multinational survey conducted in clinical practice that is designed to capture current disease management, disease burden, and associated clinical and physician-perceived treatment effects. The survey links physician-reported and patient-reported data. The DSP methodology has been described, validated, and demonstrated to be representative and consistent over time in several studies, including in various disease areas and countries.12–14

Study Design and Survey Population

In this observational study, a cross-sectional survey of PLwO and their physicians was conducted between October 1, 2023, and April 4, 2024, in the UK.

To be eligible for participation, physicians were required to be personally responsible for management and treatment decisions for PLwO, and to have consultations with at least 10 PLwO in a typical month. To be eligible, physicians could belong to the following disciplines: general practitioner or internist, diabetologist or endocrinologist, cardiologist, and obstetrician or gynecologist.

Participating physicians completed an online questionnaire to record information for 8 PLwO presenting consecutively for consultation who met the eligibility criteria for the survey. To be eligible, at the time of data capture, PLwO were required to be at least 18 years old and on a weight management program, and to have a current or previous diagnosis of obesity (defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2) or a current or previous BMI ≥27 kg/m2 with at least 1 comorbidity that was considered weight-related by their physician. A weight management program was defined as any structured attempt to lose weight, whether prescribed by a healthcare professional or not, and not restricted to a pharmacological intervention. PLwO were permitted to be receiving anti-obesity medication but not to be involved in a clinical trial for obesity treatment.

Only information available to the physicians at the time of consultation was collected, which included information from PLwO during consultation and retrospective data from medical records. The same PLwO for whom physicians had recorded information were invited to complete paper questionnaires immediately after consultation.

Ethics

All participants (physicians and PLwO) provided informed consent to take part in the survey. However, information recorded by physicians about PLwO who declined the survey could also be included in the DSP database. Ethics exemption from Pearl Institutional Review Board (Pearl IRBTM; #22-ADRW-136) was obtained for use of anonymized and aggregated data.

Outcomes

Demographic and clinical characteristics: Demographic and clinical characteristics including age, sex, BMI, and race/ethnicity were reported by physicians for their consulting PLwO. In the questionnaires provided, PLwO self-reported their employment status and type of health insurance cover (if any).

For analysis of groups defined by BMI, PLwO with available data were stratified as follows: overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2); obesity class I (30 to <35 kg/m2); obesity class II (35 to <40 kg/m2); and obesity class III (≥40 kg/m2).

Comorbidities: Weight-related comorbidities were reported by physicians (Supplementary Table S1). In this analysis, cardiovascular (CV) and metabolic comorbidities were of key interest. The following conditions were considered to be relevant CV comorbidities: atherosclerotic CVD, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, dyslipidemia, heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, stable angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, unstable angina, and vasculitis. Metabolic comorbidities were edema, hyperglycemia, hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, polycystic ovary syndrome, prediabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, and type 1 diabetes and T2D. Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology were used to inform the grouping of conditions as CV comorbidities. American Diabetes Association and Endocrine Society guidelines were used for the grouping of conditions as metabolic comorbidities.

Groups of PLwO were defined by the presence of comorbidities as follows: the “CV comorbidity” group included individuals with at least 1 CV comorbidity, and the “no CV comorbidity” group included only individuals without any CV comorbidity. The same was true of the groups with and without metabolic comorbidities. The broader “CV and/or metabolic (CVM) comorbidity” group included all individuals from the CV and metabolic comorbidity groups, and the “no CVM comorbidity” group included only individuals without any CVM comorbidities.

Health-related quality of life: PLwO completed the standard version of the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2) to measure HRQoL.15 This instrument has a 4-week recall period, and comprises 8 subscale scores (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health, plus the physical component summary [PCS] and mental component summary [MCS] scores). Scores are norm-based and interpreted in relation to the general population of the United States (US) in 2009, with a mean of 50 and an SD of 10.16 A T-score of 47 to 53 is considered within the ‟normal" range for the general population in the US. T-scores of less than 47 are considered to indicate impairment within that domain or health dimension.

Work productivity: PLwO completed the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP) questionnaire17 to assess the impact of obesity on work productivity and regular activity. The WPAI:SHP quantifies impairment of regular activity in all respondents, and absenteeism (work time missed), presenteeism (reduced effectiveness at work), and overall work impairment (related to absenteeism and presenteeism) in respondents who are in employment. The scores range between 0% for no impairment and 100% for complete impairment.18

Statistical Analysis

All available data in the study period were analyzed; no sample size calculations were performed because the analyses were primarily descriptive in nature. Statistical comparisons were performed to compare HRQoL and work productivity scores between groups of PLwO stratified by BMI or the presence of comorbidities. Analysis of variance was used to compare SF-36v2 and WPAI:SHP scores across groups defined by BMI. Bivariate comparisons of SF-36v2 and WPAI:SHP scores between each comorbidity group and the corresponding group without comorbidities were conducted using t-tests. For all comparisons, a P value <.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Recruitment and Baseline Characteristics

In total, 94 physicians provided data for 904 PLwO. Most physicians were general practitioners or internists (n = 57; 61%), approximately one-fourth were endocrinologists or diabetologists (n = 25; 27%), and the remainder comprised cardiologists (n = 11; 12%) and 1 obstetrician/gynecologist (1%).

In the group of 904 PLwO, the mean (SD) age was 51.7 (14.6) years and 490 (54%) were women; the majority of PLwO were of White race/ethnicity (n = 624; 69%) (Table 1). In total, 889 PLwO provided information on the use of medications or other approaches for weight loss when surveyed. Most PLwO (n = 689; 78%) were not prescribed medications specifically for weight loss at the time of the survey. The remainder (n = 200; 22%) reported being prescribed medications for weight loss (orlistat: n = 105 [53%]; semaglutide: n = 68 [34%]; liraglutide: n = 24 [12%]; naltrexone/bupropion: n = 4 [2%]).

Data on BMI were available for 888 PLwO at the point of consultation, of whom 109 (12%) had overweight; 308 (35%) had obesity class I; 246 (28%) had obesity class II; and 225 (25%) had obesity class III.

Overall, 442 PLwO (49%) had a CV comorbidity, 385 PLwO (43%) had a metabolic comorbidity, 637 PLwO (70%) had at least 1 CVM comorbidity, and 267 (30%) had no CVM comorbidity (Table 1). A greater proportion of men than women had CV comorbidities (53% vs 46%), but proportionally more women than men had metabolic comorbidities (59% vs 41%). The mean age of PLwO with CV comorbidities was greater than in those without (57 years vs 47 years) (Table 1).

In total, 119 PLwO completed the survey. Of 117 PLwO who answered the survey question on employment status, 78 (67%) reported that they worked full-time or part-time. Data on health insurance were available for 77 PLwO, most of whom (n = 70; 91%) reported having no private insurance and having access to the UK NHS only.

Health-Related Quality of Life

In total, 119 PLwO completed the SF-36v2. Domain and summary scores for the overall study population are shown in Table 2. Nearly all scores for the overall population fell below the lower limit of the normal range in the general US population (range: 47-53), indicating poorer HRQoL.

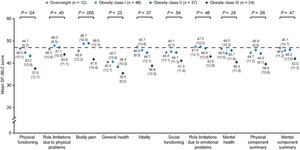

SF-36v2 data for PLwO with available BMI measurements are shown in Figure 1. The mean (SD) physical functioning score decreased with increasing BMI (overweight, n = 12: 46.5 [10.1]; obesity class I, n = 46: 44.7 [9.2]; obesity class II, n = 37: 43.2 [10.9]; obesity class III, n = 24: 37.6 [12.7]; P = .04). When only groups with obesity were considered, mean SF-36v2 scores were lower for each successive obesity class in the domains of role limitations due to physical problems, vitality, general health, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and the PCS.

PLwO with CV comorbidities (n = 52) had lower SF-36v2 scores than those without (n = 67) (Figure 2A), with P values <.05 for physical functioning (37.8 [11.7] vs 47.0 [8.1]; P < .001), role limitations due to physical problems (43.8 [11.2] vs 49.0 [8.7]; P = .005), bodily pain (44.5 [12.4] vs 49.0 [9.9]; P = .03), general health (36.6 [11.3] vs 40.7 [9.3]; P = .03), vitality (41.0 [11.6] vs 46.5 [10.1]; P = .007), and the PCS (40.0 [10.4] vs 47.1 [8.0]; P < .001).

PLwO with metabolic comorbidities (n = 65) had lower SF-36v2 scores than those without (n = 54) (Figure 2B), with P values <.05 for role limitations due to physical problems (44.6 [11.2] vs 49.3 [8.2]; P = .01), general health (36.9 [11.0] vs 41.3 [9.1]; P = .02), social functioning (42.2 [12.4] vs 46.6 [8.6]; P = .03), mental health (42.4 [12.1] vs 46.6 [9.5]; P = .040), and the MCS (43.2 [12.2] vs 47.6 [9.5]; P = .03).

SF-36v2 scores were lower in PLwO with at least 1 CVM comorbidity (n = 88) than in those without (n = 31), with P values <.05 for physical functioning (41.6 [11.5] vs 46.9 [7.3]; P = .02), role limitations due to physical problems (45.2 [10.5] vs 50.9 [7.8]; P = .007), general health (37.7 [11.0] vs 42.3 [7.4]; P = .04), and the PCS (42.6 [10.2] vs 47.9 [7.2]; P = .009; Figure 2C).

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Of the 119 PLwO who answered the relevant survey question, 8 (7%) reported being unemployed, on long-term sick leave, or retired owing to their weight. A total of 117 PLwO answered the WPAI:SHP question on activity impairment: the mean (SD) score was 36.7 (29.3). Among PLwO who reported being employed and answered the relevant questions, the mean (SD) score was 28.1 (24.1) for presenteeism (n = 75) and 5.5 (18.5) for absenteeism (n = 66). For the 65 PLwO with scores for both presenteeism and absenteeism, the mean (SD) score for overall work impairment was 32.0 (26.9).

In general, there were higher WPAI:SHP scores for activity impairment, presenteeism, and overall work impairment in groups with obesity than in those with overweight, but sample sizes were relatively small (range: 8-45), there was no apparent stepwise relationship between WPAI:SHP scores and BMI, and the P values for these comparisons were above the threshold of .05 (Supplementary Table S2).

Mean WPAI:SHP scores for activity impairment, absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment were higher in PLwO with a CV comorbidity than in those without (Figure 3); however, the P values for these differences were above the threshold of .05. All WPAI:SHP scores were also higher in PLwO with a metabolic comorbidity than without, with P values <.05 for activity impairment (43.0 [30.7] vs 29.3 [25.8], P = .01) and presenteeism (33.7 [25.5] vs 20.6 [20.2], P = .02; Figure 3).

All mean (SD) WPAI:SHP scores were lower for PLwO with at least 1 CVM comorbidity than for those without these comorbidities, particularly for activity impairment (41.0 [29.3] vs 24.5 [25.8], P = .007), overall work impairment (36.0 [26.2] vs 19.7 [25.7], P = .03), and presenteeism (33.0 [23.8] vs 15.7 [20.6], P = .005; Figure 3).

The sample size, median, and interquartile range for overall WPAI:SHP scores and scores grouped by the presence or absence of comorbidities are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

DISCUSSION

This real-world analysis using data collected from both physicians and individuals receiving weight management support provides valuable insights into the different effects of BMI and comorbidities on PLwO. Higher BMI was linked to worse HRQoL, particularly physical functioning, but the relationship between BMI and work productivity was less clear. The presence of comorbidities in the PLwO group affected both HRQoL and work productivity, and the exact nature of these effects varied slightly between CV and metabolic comorbidities. In addition to addressing a key evidence gap concerning the impact of comorbidities on HRQoL and work productivity in obesity, our results support existing data indicating a negative correlation between BMI and HRQoL.

Previous observational studies using different measures of HRQoL have indicated that higher BMI is linked to worse HRQoL in PLwO. In the UK, Health Survey for England data suggested that higher BMI in PLwO was associated with lower EQ-5D-3L summary scores.19,20 In the US, studies using the SF-36v26 and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health metric21 reported that HRQoL in PLwO decreased with increasing BMI.

The SF-36v2 data in our study are supported by a previous analysis with a much larger sample size.22 In our study, PLwO with higher BMI reported poorer SF-36v2 scores in most domains, particularly for physical functioning, and this result is similar to those from a meta-analysis that included 43 086 adults from multiple countries and showed reduced HRQoL in PLwO, particularly in the physical domains.22 However, some of our findings differ from published data. In our study, nearly all the mean SF-36v2 scores in PLwO were lower than the normative value of 47 for the general population in the US in 2009,16 suggesting impairments in HRQoL domains. These findings differ from those of randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy of semaglutide (STEP trials) or tirzepatide (SURMOUNT trials) for weight management in PLwO that reported baseline SF-36v2 domain scores for participants. In STEP-1, STEP-2, STEP-3, and STEP-4, all SF-36v2 domain scores were reported,23,24 whereas in the SURMOUNT trials (SURMOUNT-1, SURMOUNT-3, SURMOUNT-4, and SURMOUNT-CN) only scores for the SF-36v2 physical functioning domain were reported.25–28 In the STEP and SURMOUNT trials, the baseline SF-36v2 scores from trial participants were all above the normative value for the US general population,23–28 which contrasts with our study. This is likely to result from disparities in populations and SF-36v2 administration methods between the clinical trials and this real-world survey.

Our study did not identify any clear stepwise relationship between increasing BMI group and reduction in measures of work productivity. However, activity impairment scores, presenteeism, and overall work impairment were generally higher in people with obesity than in those with overweight. These findings are concordant with the apparent relationship between increasing BMI and reduced physical functioning identified in our study, and are consistent with published data.6

There are few published data on the impact of comorbidities on HRQoL or work productivity in PLwO. In a previous US study, people with obesity and T2D reported poorer HRQoL and impaired work productivity than those with obesity without T2D.6 In our study, comorbidities appeared to have an impact on all aspects of HRQoL and work productivity, but there were some differences between CV and metabolic comorbidities. For example, there was an apparent significant reduction in the PCS score in the group with CV comorbidities, but not in the PCS score for the group with metabolic comorbidities. This finding supports a holistic approach to the management of overweight and obesity that considers the presence of comorbidities in addition to BMI, and seeks to treat concomitant conditions alongside weight management support. This approach aligns with a position statement published in 2025 by Rubino et al proposing that impairments of organ function and activities of daily living related to excess weight, in addition to indices of body fat, should be considered when diagnosing and treating obesity.29

The results of this study should be considered in the context of the wider societal impact of obesity in the UK. Between 1992 and 2020, successive UK governments proposed 689 wide-ranging policies to address obesity in England alone; however, the prevalence of obesity has continued to rise, particularly in certain socioeconomic groups.30 In 2020, the UK government recognized that overweight-related and obesity-related conditions across the UK cost the NHS £6.1 billion annually, and estimated that weight loss of 2.5 kg for individuals who are living with overweight or obesity could save the NHS £105 million in the next 5 years.31 The treatment landscape for obesity in the UK has also undergone changes with the approval of semaglutide and tirzepatide for weight loss in obesity in the UK in January 202232 and November 2023,33 respectively. Follow-up analyses aligned with the present study would be valuable to assess how the availability of these medications has affected PLwO who are eligible for weight management interventions.

The Adelphi Real World Obesity DSP captures a broad range of characteristics for PLwO, allowing both characterization of the population and identification of risk factors for disease burden. However, our study has some limitations. The population of interest includes only PLwO receiving weight management support, meaning that the results may not be fully generalizable to the wider population of PLwO in the UK. Furthermore, data capture is based on PLwO presenting to the physician in the specified time frame, which may have led to PLwO who consult more frequently being selected for the study. The low completion rate for some questions limited the available sample size, introducing the possibility of selection bias and reducing the power of statistical comparisons. Finally, the cross-sectional observational study design limits the ability to determine causality in relationships between clinical characteristics and HRQoL or work productivity, and further research with larger and broader populations is warranted to address this.

CONCLUSIONS

This real-world study indicates that both BMI and comorbidities in PLwO are likely to affect well-being and daily life. This suggests that these factors should be considered as part of decision-making regarding the individual clinical management of overweight and obesity, as well as wider societal efforts to understand the impact of overweight and obesity and to reduce the effects of both conditions in the UK. Furthermore, the findings suggest that reducing the prevalence of overweight and obesity and limiting the development of comorbid conditions could bring benefits for both individual health and wider society.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Michael Lee, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, with funding from Novo Nordisk A/S in accordance with the Good Publication Practice 2022 guidelines. Statistical support was provided by Emily Quinones of Adelphi Real World, Bollington, Cheshire, UK.

Funding

This analysis was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S. Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the "Adelphi Real World Obesity Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP). The DSP was funded, and is wholly owned, by Adelphi Real World. Novo Nordisk A/S is one of multiple subscribers to this data set. Novo Nordisk A/S did not influence the original design or data collection of the DSP data in any way. All authors contributed to the design of the analyses, data interpretation, and critical review and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

Conflicts of Interest

A.L. and L.H. are employees of Adelphi Real World. Adelphi Real World received funding from Novo Nordisk A/S to perform this analysis. J.D.R.F., C.L., and S.C. are employees of Novo Nordisk A/S, and J.D.R.F. and S.C. are also shareholders of Novo Nordisk A/S. L.M.H. is an employee of Novo Nordisk Region Europe and Canada.

Data Sharing Statement

All data relevant to the analysis are included in the article. All data that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request to Lewis Harrison at lewis.harrison@adelphigroup.com.

_cv__(**b**)_metabolic__or_(**c**)_cvm_comorbidities.jpeg)

_activity_impairment__(b)_presenteeism__(c)_absenteeism__and_(d)_ov.jpeg)

_cv__(**b**)_metabolic__or_(**c**)_cvm_comorbidities.jpeg)

_activity_impairment__(b)_presenteeism__(c)_absenteeism__and_(d)_ov.jpeg)